A half step from horror

On Instalove, penny dreadfuls, and female nightmares

It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of the romance genre. As a whole, I find it a hopeful and empowering space filled with authors and readers who are free with their encouragement and support. It’s a primarily female space, and because of the primacy of the Happily Ever After (HEA) it’s a place where women can engage in critical thought about the issues we face with the assurance that, at least for this character, things will turn out alright in the end.

Feminist fiction

I firmly believe that the most common criticisms of the genre are wildly problematic. First, the accusation that romance novels are porn falls neatly into ideas that women’s pleasure and sexuality is inherently dirty, sinful, and shameful. Sex isn’t porn, and dismissing a whole genre that spans a spectrum from the closed door longing of Jane Austen to the kink of Katee Robert isn’t a legitimate criticism.

The second most common criticism is, I think, at the heart of the first. It stems from both men’s insecurities and women’s grief: that romance novels teach women to expect too much of men. Call me a crazy feminist, but I like to think that men are as capable of the breadth of human emotion and personal growth as much as women are. Imagining a man who is willing to show up and do the work to be a supportive and loving partner shouldn’t be seen as a fantasy.

We listen and we don’t kinda judge

Now, I’ll go to bat for romance, but just because I think that most criticisms are rooted in patriarchal and misogynist expectations doesn’t mean there aren’t some issues in the genre. If you’ve read Isn't it romantic or Trouble in Paradise, you know how I feel about dark romance. Today, I want to talk about Instalove.

Instalove, formerly Love At First Sight, can be a sweet trope, heavy on nostalgia and low on angst. There’s a huge appeal to the idea that someone sees you, really sees you, and loves what they see enough to go all in. Smitten characters, particularly smitten men (He Falls First, anyone?) are a sort of balm when you’re feeling jaded by the real world. But Instalove is turning up in a particular sort of romance these days, and the more I see it, the more bothered I am.

The story goes like this: He sees her in town and knows that she belongs to him. She isn’t so sure at first, but he’s handsome and protective and affectionate, and she has always wanted a family. She’s usually less experienced, often a virgin. On some pretext, he gets her into his house, then into his bed. Within days, they’re married, and soon she’s pregnant, the whole story tied up in a bow in eight chapters.

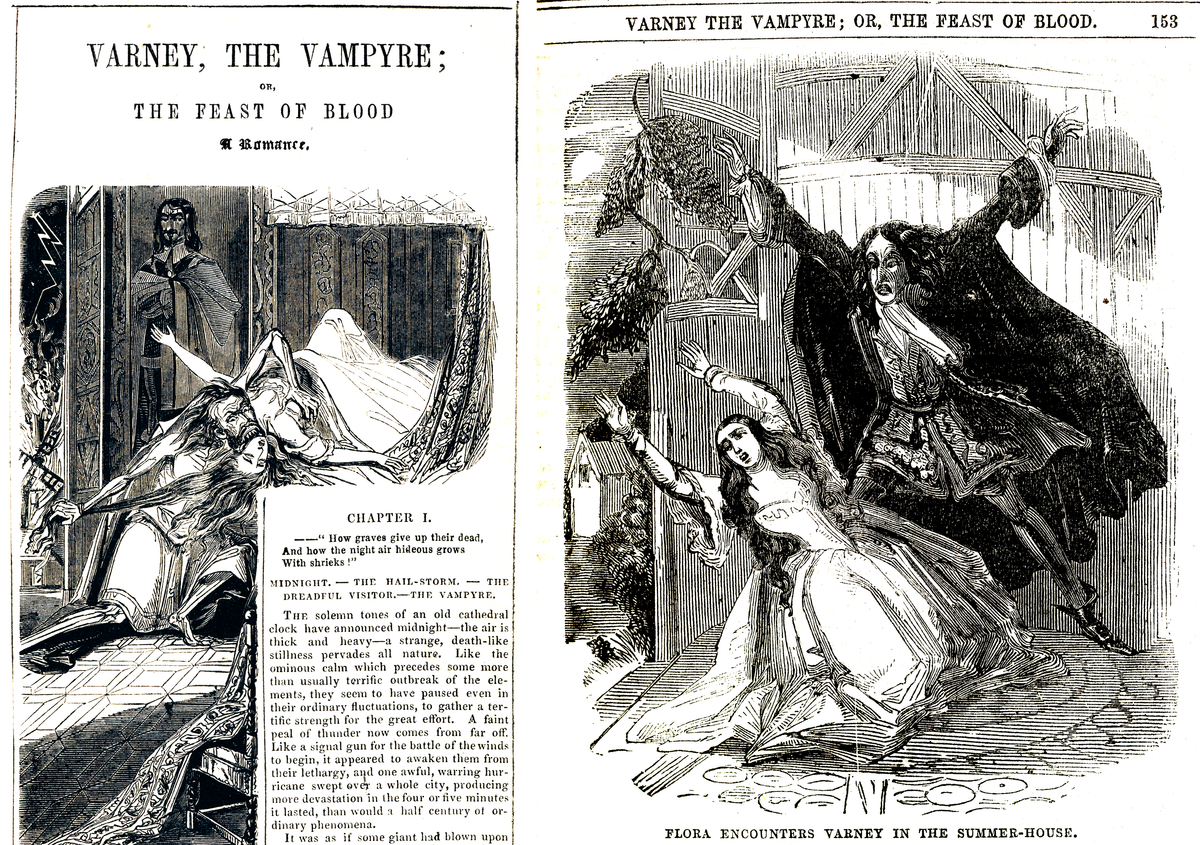

Penny Dreadful

Generally these Instaloves are published in quick succession, book after book running through the character’s friend groups or siblings as they topple like dominos into relationships to the tune of “When you know, you know!” The eight chapter format seems to be especially popular, and I have to wonder if it’s a nod to the Victorian penny dreadfuls. These lurid stories heavy on murder, blighted romance, and tragedy, were released one page at a time and finished in eight installments. Stories of monsters, criminal gangs, and corruption reigned. Penny dreadfuls, like many of today’s ebooks, were cheap and easily accessible. They had a reputation for poor writing, melodrama, and sensationalism. Initially marketed to the newly literate working poor, the format eventually shifted to adventure stories for boys.

Most penny dreadfuls are lost like the ephemera they were, but we still have some. Sweeny Todd originated in a penny dreadful. If you’ve read Little Women, you may remember Professor Bahr’s admonition of Jo over her authorship of a dramatic serial. Louisa May Alcott did, indeed, write penny dreadfuls. She had mouths to feed, and sensationalism and gore, then, as now, pays the bills. A Long and Fatal Love Chase, deemed too sensational for publication during Alcott’s life even under her pseudonym, is a nod to the penny dreadful in novel form and a fascinating look at the lurid 19th century tales.

Penny dreadfuls were viewed suspiciously by many, and by the latter half of the 19th century were a source of moral panic similar to the reactions to comic books, video games, and, you guessed it, romance novels. “Perhaps it wasn’t what was being read so much as who was reading it that lay at the root of society’s unease.” Hepzibah Anderson writes for the BBC. Amen, sister! Authoritarian societies are always extra concerned that what women, children, and the lower class read will continue to uphold whatever authoritarian values are already in place.

A half step from horror

Let’s jump back to our Instalove. I’m not sure if it’s because the swirling miasma of “underage women” rapespeak has ratcheted up thanks to current events, or the discussion of how love bombing and grooming work in intimate relationships, but under the shiny HEA veneer, all I can see are real life headlines, because friends, this is not romantic behavior, it’s red flags out the wazoo. When he manipulates her into his home, I think of women escaping to DV shelters with toddlers on their hips. When he’s angry that another man hits on her, I think of men choking their wives and when that wife escapes she’s told by a judge it couldn’t have been so bad if she had that many kids with him. Violence against women is baked into our society, and while romance can be a good place to examine that, this isn’t examination.

I’m not interested in feeding moral panic, but shit is shit regardless of where you find it. While I personally don’t have a very high tolerance for horror as a genre (my nervous system really runs with the “nervous” bit) I would be so much more comfortable with these stories if they took that last half step into horror. Calamity is the bread and butter or the penny dreadful, happiness a fleeting precursor to tragedy, and I can’t stop expecting the other shoe to drop in these Instaloves. These don’t read like romances to me, they read like unfinished penny dreadfuls, moral tales with warnings of the sorts of men to be wary of. The ending isn’t written in the story, it’s in the DV stats, the family annihilation headlines, the quiet community tragedies I’ve watched unfold again, and again.

I love how you layer all of these ideas, especially the connection with the Penny Dreadful and how insta love books are getting turned out.

Great piece. Very interesting and informative.